This is one of 20 chapters from my book, “River of Offerings,” which, through stories and pictures, tells the story of 12 adventures up and down the Ganges River (known in India as the Goddess Ganga). These events take place over a ten-year period, as a means of understanding the roots of the practice of yoga and what it means to live a meaningful life. To purchase the book or for more information about this project, visit the Kickstarter page.

Row, row, row your boat, gently down a stream,

American Nursery Rhyme from the mid-eighteenth century

Merrily merrily, merrily, merrily, life is but a dream.

Faisal, Gajender, and I ascend by minivan up an unruly road resembling a long strand of Shiva’s hair. We traverse dense jungle and expansive rice fields that slowly give way to large, coniferous trees that populate what becomes, over the next twelve hours, a treacherous landscape reaching 12,000 feet at Gangotri. This is one of four sites on a pilgrimage circuit which has been heavily traveled by wandering ascetics since the eighth century, when the Hindu saint Shankaracharya was here. The Chota Char Dham circuit was well known for hundreds of years to Hindus who lived on the plains below, but these sites were not a visible aspect of yearly religious culture, largely because the journey is difficult. After the war between India and China in 1962, India undertook extensive road building in the border areas, making the Chota Char Dham accessible by car.

Narrow roads host tour buses packed with families from Delhi, cars, cows, goats, sheep, and their herders, seven-year-old girls harvesting rice, motorcycles with, most often, two Sikh men per bike. Wearing orange head scarves, the Sikhs usually head to Gurudwara Hemkund Sahib, a sacred Sikh site down the road from Gangotri. Pandits, Hindu priests well versed in the Vedas and the great Hindu epics, used to accompany pilgrims from Uttarkashi, offering the retellings of the Ramayana and Mahabharata. Today, while sadhus walk miles by foot, and pause at tirthas that dot the roadside, linking physical location with the transcendent, Indian families watch TV adaptations of the Ramayana and Mahabharata in their cars as they drive up the mountains. Once the rains begin, travel to this area becomes next to impossible. Every ten minutes or so, the Himalayan Authority has posted a road sign stating the obvious: “Keep your nerves on the sharp curves!” “Drive with care, life has no spare!” and “If you sleep, your child will weep!” A few more hours and few more road signs, and we are up so high that if you fell from these cliffs, you would have time to see an entire life pass before your eyes on the way down. The roads are closed at night because it’s simply too dangerous to drive. It’s also too dangerous during the day, when one, two, or three large tour buses barrel down the single lane road with no guardrail on the exposed side. We pass a line of tin shacks that hang on a cliff ledge. Children play on piles of dirt while women hang laundry on a rope tied between two trees. These families are from Nepal or Bihar. They work cement around large rocks by hand, forming a rock wall which will hold the mountain at bay until the next big storm.

Narrow roads host tour buses packed with families from Delhi, cars, cows, goats, sheep, and their herders, seven-year-old girls harvesting rice, motorcycles with, most often, two Sikh men per bike. Wearing orange head scarves, the Sikhs usually head to Gurudwara Hemkund Sahib, a sacred Sikh site down the road from Gangotri. Pandits, Hindu priests well versed in the Vedas and the great Hindu epics, used to accompany pilgrims from Uttarkashi, offering the retellings of the Ramayana and Mahabharata. Today, while sadhus walk miles by foot, and pause at tirthas that dot the roadside, linking physical location with the transcendent, Indian families watch TV adaptations of the Ramayana and Mahabharata in their cars as they drive up the mountains. Once the rains begin, travel to this area becomes next to impossible. Every ten minutes or so, the Himalayan Authority has posted a road sign stating the obvious: “Keep your nerves on the sharp curves!” “Drive with care, life has no spare!” and “If you sleep, your child will weep!” A few more hours and few more road signs, and we are up so high that if you fell from these cliffs, you would have time to see an entire life pass before your eyes on the way down. The roads are closed at night because it’s simply too dangerous to drive. It’s also too dangerous during the day, when one, two, or three large tour buses barrel down the single lane road with no guardrail on the exposed side. We pass a line of tin shacks that hang on a cliff ledge. Children play on piles of dirt while women hang laundry on a rope tied between two trees. These families are from Nepal or Bihar. They work cement around large rocks by hand, forming a rock wall which will hold the mountain at bay until the next big storm.

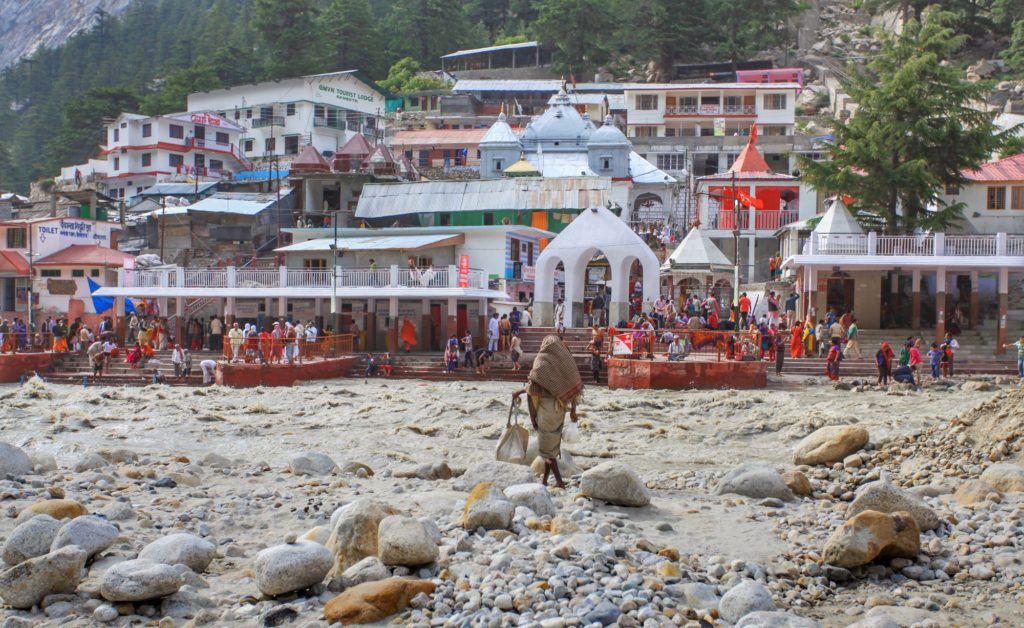

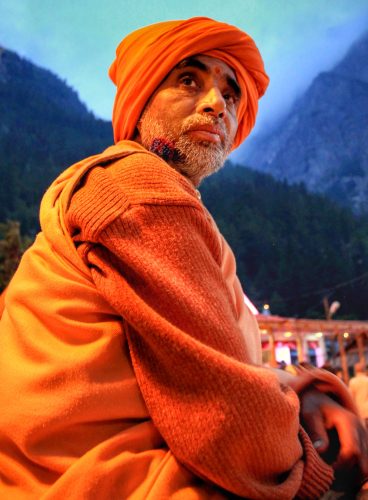

Ten hours later, we park the car at Gangotri, the first village of Ganga, filled with market stalls selling small copper containers to hold river water that will return home with pilgrims, and all the accouterments needed for a river arti. Up here the river is known as Bhagirathi, and it is raging. The people who have come all this way for a holy dip could be swept away in a second. Gomukh Glacier is about eighteen kilometers (around 11 miles) higher than Gangotri, and is largely recognized as the origin of the river. However, climate change is melting the glacier. Some of the fastest-melting glaciers in the world are in the Himalayan mountain range. Himalayan snow and ice, which provide vast amounts of water for agriculture in Asia, are expected to decline by twenty percent by 2030.  Faisal and I walk to the stone temple built in 1800 by a Sikh General, Amar Thapar Singh, on the place where King Bhagiratha performed his penance, or tapasya, by standing on one leg for 1000 years. Inside and outside, every square foot is lit up by cycling-colored LED lights. A middle-aged, bearded sadhu invites me to sit beside him. I sit in padmasana, or lotus posture, and he follows. With a little bit of English, he says that he walks the road half the year, and is in Gangotri the other half. Our language is not fluent enough to know whether sitting in padmasana holds the same meaning, but we’re together and that’s all that’s important. The crowd waves their arms in the air as the arti progresses. Inside the temple, two men call in the elements, air, water, and fire; Faisal explains that the earth element isn’t called in this ceremony because we are standing on it. The LEDs are pulsing pink, blue, yellow, and green over the faces in the crowd like an outdoor disco in the late 1970s. My attitude may be colored by the encroaching altitude sickness or the ominous feeling of standing under a menacing sky. I walk back to my room. No heat, no light, nothing remotely close to comfort, except my new purple sleeping bag filled with geese down that I stuffed in the suitcase. I awaken at 4 am from a nightmare. As odd as it sounds, a voice in the dream says not to go on to Shiva’s abode, Kedarnath. My bones feel cold.

Faisal and I walk to the stone temple built in 1800 by a Sikh General, Amar Thapar Singh, on the place where King Bhagiratha performed his penance, or tapasya, by standing on one leg for 1000 years. Inside and outside, every square foot is lit up by cycling-colored LED lights. A middle-aged, bearded sadhu invites me to sit beside him. I sit in padmasana, or lotus posture, and he follows. With a little bit of English, he says that he walks the road half the year, and is in Gangotri the other half. Our language is not fluent enough to know whether sitting in padmasana holds the same meaning, but we’re together and that’s all that’s important. The crowd waves their arms in the air as the arti progresses. Inside the temple, two men call in the elements, air, water, and fire; Faisal explains that the earth element isn’t called in this ceremony because we are standing on it. The LEDs are pulsing pink, blue, yellow, and green over the faces in the crowd like an outdoor disco in the late 1970s. My attitude may be colored by the encroaching altitude sickness or the ominous feeling of standing under a menacing sky. I walk back to my room. No heat, no light, nothing remotely close to comfort, except my new purple sleeping bag filled with geese down that I stuffed in the suitcase. I awaken at 4 am from a nightmare. As odd as it sounds, a voice in the dream says not to go on to Shiva’s abode, Kedarnath. My bones feel cold.

I call my husband in tears to tell him the dream. He says I’d be disappointed if I don’t go to Kedarnath. While I hear his words, everything inside says something else. Faisal knocks on the door. I repeat the telling of the dream. With disappointment bordering on frustration, he says, “You do not have the faith of the sadhus. These people climb mountains because they know that Ganga will take care of them. You need to have more faith.” He orders hot water and leaves me alone to shiver naked in the tiny bucket of river water, submerged like a baby elephant in a tiny upside-down podium. I’m bewildered and wonder if the water in this bucket is Ganga herself, and if so, will she forgive my lack of faith? Faisal also summons a doctor who confirms fever and a bacterial infection, another way of saying that the rivers in the body have gone toxic. Five days on antibiotics and I should be “right as rain.”

I brought the book, Comfortable with Uncertainty: 108 Teachings on Being a Spiritual Warrior by Pema Chodron, a woman from Quebec who became a Tibetan Buddhist nun and whose lineage comes from just over these mountains. Her writing is appropriate when you feel beside yourself with grief or fear, or when you are sick in high mountains with no internet on your birthday. She writes about learning how to be cool when the ground beneath you disappears; how to use discomfort as an opportunity for awakening; and how to see the path itself is the goal. I can’t do a lot up here, but I can work with fear and a blazing fever in a stark room for thirty-six hours.

Two days in, and I’m well enough to be moved. Though this decision will be unpopular, I do not feel as though I know the goddess of this river on a first name basis. I can’t feel her, like the people along her banks seem to. What I have learned is to trust the “still small voice within,” for lack of a better term. I know that the practice of yoga helps to distinguish between thoughts that repeat themselves often and deeper moments of clarity.

I recognize an essential truth. Despite the disappointment that I may cause my husband, travel guide, and the goddess Ganga herself, if I look toward the end of my life, which right now is quite easy to envision, I want to feel that I had the courage to live by an inwardly abiding truth. I may have a pittance for a practice in comparison with the holy men who walk these mountains, but it’s going to have to be enough. I return to the van to descend these mountains. I shall take my own course. I do not tell anyone, but I am not going to Kedarnath.

Learn more about Jennifer Prugh’s passion project here.

One reply on “Excerpt From My New Book “River of Offerings””

I am thankful for your “still small voice within”, because it perhaps saved your life that day. Although, I would debate it being small. I think it’s trustworthy and brilliant and rather large. This story of you following your intuition is a testament of how you live your yoga, a daily practice of listening within. And this book? It’s outstanding artistry.