A five-part world history lesson – part four. (Read parts one, two, and three, here.)

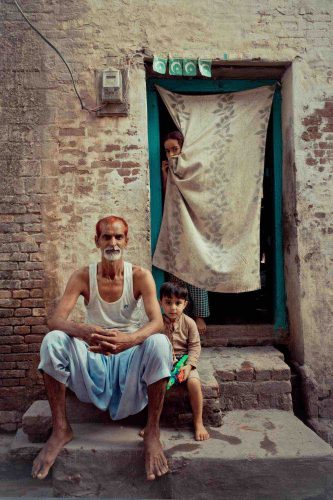

We finished the last installment back in 1893 at the Chicago World’s Fair and the World Parliament of Religion. We’d just met a 30-year-old, self-proclaimed Indian swami by the name of Vivekananda. Vivekananda was born Naren Datta in Calcutta to an upper-middle-class family. He was educated in British-run schools and so had a thoroughly Western-style education and spoke impeccable English. Late in 1881, Naren had an encounter with a very strange individual, the Indian saint (some would say madman) Ramakrishna, and it changed his life forever. Ramakrishna, then in his late 40s, was an attendant at a temple near Calcutta and something of a local celebrity. Born into a poor, rural brahmin family and given to samadhi-like trances from a very early age, he’d collected around him a circle of young Indian men who worshiped him as an avatar, an incarnation of God. At first, Naren was completely put off by the rough-hewn, uneducated wild man, but, for his part, Ramakrishna fell immediately in love with the puppy-eyed teenager. Eventually, Naren came to terms with Ramakrishna’s bizarre behavior, joined his circle, and became the saint’s star pupil. But the relationship was relatively short-lived – Ramakrishna died of cancer in 1886, leaving his followers to their own devices.

The young men were at loose ends after the death of their master but soon banded together as a fellowship of monks. In 1888, as is traditional after taking such vows, Naren set off on a walking tour of India, finally reaching the southernmost tip of India near the end of 1892. After meditating there for three days, he resolved to dedicate the rest of his life to improve the lot of India’s impoverished masses. To this end, he was urged to bring his message to the West. So in May of 1893, now calling himself Swami Vivekananda, he set off across the Pacific and landed in Vancouver in late July, then set off by train for Chicago. To his dismay, he discovered a couple of monkey wrenches in his plan. One, he was way early – the Parliament wasn’t scheduled to convene for another six weeks – and two, only invited delegates would be allowed to speak. His only route to a seat on the podium was closed, since the delegate selection committee had already disbanded. So there he was, alone in a strange city with nowhere to go, nothing to do, and running low on money.

Fortunately, on the train ride from Vancouver, he’d met Katherine Sanborn, a well-connected former college professor, who’d invited him to visit her in Massachusetts. Vivekananda beat a strategic retreat and hopped a train for Boston, where he was welcomed by and taken under the wing of Miss Sanborn. With his boyish good looks, exotic robe and turban, and impressive grasp of Indian philosophy, Vivekananda was quite a hit with his host’s friends and associates. His charm and intelligence captivated John Wright, a professor of Greek at Harvard, who wrote Vivekananda a letter of recommendation to the World Parliament organizers and bought him a ticket back to Chicago. Vivekananda left Boston on September 7th, just a few days before the Parliament’s opening ceremony. But when he detrained in Chicago, he discovered, again to his dismay, that he’d lost both Wright’s letter and the address of the contact person the professor had arranged for him. The story goes that he spent the night in the rail yard in a boxcar, went out begging for his breakfast the next morning – apparently not too successfully, since a robe and turban in late-19th century Chicago alarmed a lot of people – and finally, in despair, did what any rational person would do in that situation: he sat down on a curb by the side of a street and waited for God to send help.

Stay tuned next week for the conclusion of this five-part series.