Tackling the Yoga Sūtras in one go can be a daunting endeavor. From experience, I have started, stopped, and restarted many times. For this reason, I decided to write a monthly piece for which I pick a Sūtra and let you know how it may be interpreted. The idea is to do so in small doses so that you can taste, swallow, and digest it before we present you with another one. Here we go!

अथ योगानुशासनम् ॥१॥

atha yogānuśāsanam.

atha = now

yoga = yoga

anu = continuation of an activity, traditionally followed, lineage

śāsanam = instruction or exposition

Now, we continue the instruction of yoga.

This first Sūtra appears seemingly simple, but the implications can go as deep as the student is willing to dive. Atha is a sacred word that opens many texts and indicates that the following teachings are delineated from those of other texts. It assumes the reader is a learned student who is now ready for the subject matter at hand: yoga, and assumes a disciplined state of mind.

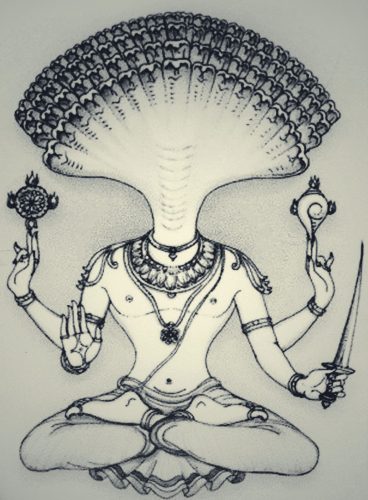

Patañjali was not an uncommon surname in his time, and it is difficult to confirm the exact details of his life. This, of course, led to the legend of Patañjali: It is said that he is the incarnation of Ādiśeṣa, Lord Viṣṇu’s serpent, who manifested into human form to experience life and impart his knowledge onto humanity. Patañjali chose to write on three subjects: grammar, Āyurveda, and yoga. Atha implies a progression of knowledge. Grammar is needed for clear comprehension, and Āyurveda is needed for cleanliness and equanimity. These works serve as a preparation for an exposition on yoga.

The term anu means a continuation of an activity, a lineage of sorts, implying that this is not an introduction to the subject of yoga for the reader. Patañjali was not the creator of the teachings of the Yoga Sūtras; rather, he is the person who systematized a pre-existing tradition already known to the audience. In fact, he sometimes cuts lists short and assumes the audience is familiar with the subject matter.

The big question is, “What is yoga?” It’s a bit early to expound on this with just the first Sūtra, but nonetheless, we can begin. Commonly translated from the root word yuj, meaning “to yoke,” many students attach this definition to the idea of the individual’s spiritual union with puruṣa, a term referring to the innermost conscious self, the soul. The predicament of our existence is that mind and soul are separate, which produces suffering. This union may also refer more generally to that of the mind with its object of concentration. Yuj also means “to contemplate,” which seems more fitting here. Ultimately, the goal in the Yoga Sūtras is not so much about union, but an unjoining or disconnecting of puruṣa from prakṛti, the material world.

The Yoga Sūtras provide practical and direct instruction, not just philosophy. He stresses that we cannot achieve our goals with philosophy alone – we must practice. Patañjali’s yoga is about attaining samādhi, enlightenment. This predates the development of haṭha yoga, which is common in the modern yoga practice. Patañjali’s yoga practice is about meditative stillness. The yoga posture, or āsana, refers simply to sitting as steadily and effortlessly as possible, so that we may focus and concentrate. However, the Sūtras are intentionally vague, packing the maximum amount of information into the minimum number of words. Ultimately, this allows the audience to color the subtext with a modern perspective, and it is this general applicability to the human experience that makes the Yoga Sūtras so ubiquitous.

Inquiring minds can dive deeper with these resources:

3 replies on “Yoga Sūtras 101: Decoding the First Sūtra”

Thank for this! I think this first one is my favorite!

Oh Shute, that comment was w/regard to your Bio, not first sutra!

Dark chocolate+espresso : )

BRILLIANT START TO THE DAY, PAPABEAR!

I’M COPYING YOU…”MY YOGA TEACHER SAID IT WAS OK!”

AMY