Asana, the third of eight limbs in yoga, has become more and more mainstream over the last decade. One-third of Americans have practiced yoga at least once. It’s popular, but because it has become so accessible, many of its benefits have unintentionally been diluted.

When I began my practice, I had little idea of what I was missing. My body was getting stronger, and I seemed to feel pretty good after class. But, then I began to hit plateaus where my body was not progressing, and I couldn’t figure out why.

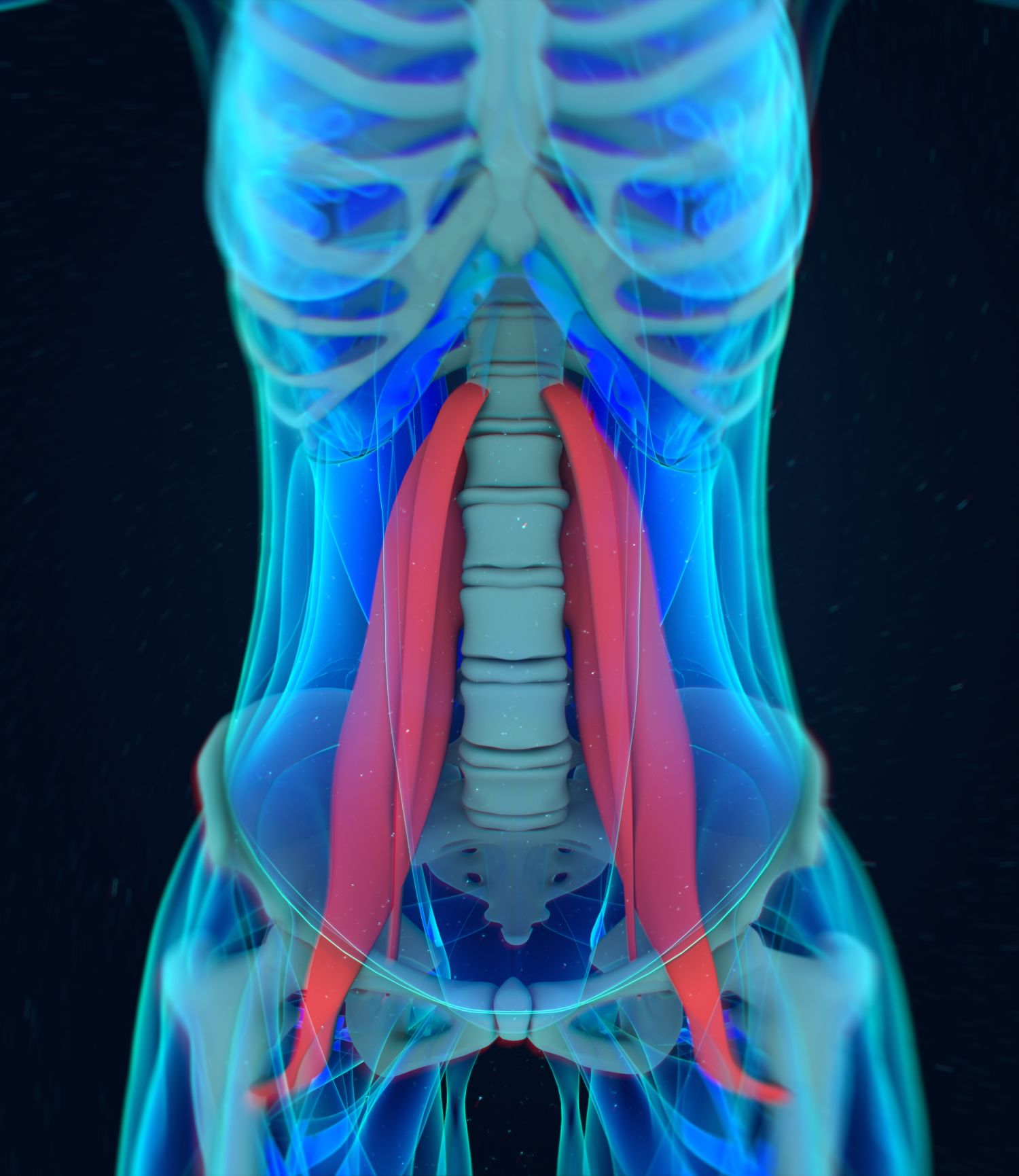

A few years later, I would find my teacher, James Brown, and his concept of The Tapas Point. Most systems in nature, such as water, electricity, and the human body, want to conserve energy, taking the path of least resistance. Because of this, your body will try to compromise in various yoga postures: with a minor bend of a knee or elbow, slight rounding of the spine, etc. These minute adjustments are how your body steps around the work that these postures offer. The Tapas Point solves this problem by beginning each position from a well-aligned base. We then move slowly, stopping at the point at which (if we were to go any further) the body would yield out of that optimal alignment.

To be clear, we’re talking about working directly at your edge, and not beyond it. I’ve read and heard many thoughts that if you work too hard in yoga, you’re creating stress and producing injuries, doing more harm than good. Injuries take place in the body because your joints and surrounding tissues have a specific, load-bearing capacity. If exceeded, the body can’t manage that force, and injury occurs. On the other hand, this approach to asana creates a safeguard in which you stop before any joint is asked to take on an excess load.

Precise alignment is significant on many levels. The first is the physical relationship. The Specificity Principle states that if you want something to change, you have to do whatever that task is. You’re not going to get much stronger in your arms by working out your legs. To increase hip extension in a low lunge, bending your knee as far as possible and rounding your low back as a consequence, is not going to help that cause. The Tapas Point allows the practice to be tailored to the individual. Whether strength or flexibility is limited, it suits the practitioner’s needs.

When it comes to yoga, this is profound because it directly correlates to what an authentic practice offers. Yoga is about focus, concentrating on one thing of the practitioners choosing. Because in a dynamic yoga class we use our bodies in many ways, optimal alignment is the perfect object for attention. Stopping just before we lose that alignment requires focusing on the present moment by concentrating on precisely what your body is doing. Additionally, this concept provides valuable information about how we manage our limitations and put our ego on display.

“Taking a step backward” is troublesome to the ego, but what is fascinating about yoga is that it can bring change.

Changing how far I go into a posture was not something my ego wanted any part of, especially in a public class. By listening to the inner dialogue taking place, you can observe what you value; for instance, choosing to focus on improving your practice, or trying to impress people next to you with a shape that somewhat resembles the suggested posture.

Implementing The Tapas Point has remarkably changed my practice and taught me things about my body I was unaware of. Because of this concept, I am able to focus better and my body has increased its strength and range of motion. More importantly, I’ve been able to see my past attachments to ideas that I don’t truly value and learned that I value change over a false sense of status. This concept has also allowed me to replace my conditioned patterning for the better, and I am very grateful for it.