Two questions students always ask me are:

- Why did you start pranayama (breathwork)?

- How have you managed to keep this practice alive now all this time?

The first question is fairly easy to answer. I started back in 1982 because pranayama was part of a teacher training program I was enrolled in at the B.K.S. Iyengar Yoga Institute (hereafter IYI) in San Francisco. In contrast to the standard 200-hour training in most schools nowadays, the program at IYI extended over two full years. If memory serves, there were three breathing classes on the curriculum, each one running for 12 weeks. One was called something like “Introduction to Breathing,” the other two “Pranayama 1 and 2.” Along with this, the weekly public class I attended at IYI, with the same teacher I went to in the program, reserved the last class of the month exclusively for pranayama. Back then, breathing was a natural part of my practice.

Things didn’t go well at first – to say the least. I took the practice very seriously, so every morning, without fail, I set myself up to breathe, mostly following the sequences at the back of Light on Pranayama. As you may know, Iyengar teachers can be very aggressive in their teaching, and my teacher (who I won’t name) was extremely close to Mr. Iyengar and taught just like him. There were no slaps, but there were plenty of other Iyengar-like pyrotechnics; including yelling, ridicule, and poses held forever and a day. I remember coming out of a headstand at the 19-minute mark of a scheduled 20-minute stay and being chastised with, “Nobody told you to come down.” At the time, we all loved it, and the aggressiveness rubbed off on me. We were told that today’s maximum is tomorrow’s minimum – and I bought into that, hook, line, and supta padangusthasana.

But, the problem for me was that aggression, especially when it came to breathing, was an epically bad idea. At the time, aged 35, I had some unresolved issues that didn’t respond well to the way I was practicing. I’d only been playing in the fields of the lord by then for two years, and, honestly, knew next to nothing about the practice. It seemed to me in my nescience (avidya) that if I pushed on myself as hard as my teacher pushed on me, I’d improve my practice faster. But this reasoning was (and still is) entirely fallacious. It might be possible to push an asana here and there, with the understanding that you’re upping your chances of an injury, but you can’t – or shouldn’t – ever push your breath. Though it was fairly obvious, I simply didn’t grok that breathing is actually an extremely powerful, transformative tool, for good or ill. For me it was the latter.

So, every day I practiced toward my new maximum, and every day I sank deeper into depression, which induced brain-splitting headaches. I had a large calendar in my kitchen on which I’d make a blue dot on the days I was in pain, and month after month, the blue dots far outnumbered the un-dotted days. In desperation, I went to the program’s meditation teacher, who kindly escorted me down to Mount Madonna for an interview with her guru, the famous, silent yogi, Baba Hari Dass. Have you ever tried to converse with someone who holds up his end not by talking? By then, he supposedly hadn’t said a single word for something like 20 years, but by writing on a little blackboard that hung on a string around his neck. I’m not making this up. He was extremely sympathetic and advised (in writing) to stop pranayama altogether for three months. This was exactly what I didn’t want to hear, and so, in my infinite wisdom, I ignored him. The pain continued, unabated.

This went on for a couple of years until I finally wised up and took the advice of several yoga friends and went to a different teacher. He was Iyengar trained (I wouldn’t have agreed to it otherwise) but he believed that yoga was more about quietly undoing than aggressively doing. Things slowly quieted down.

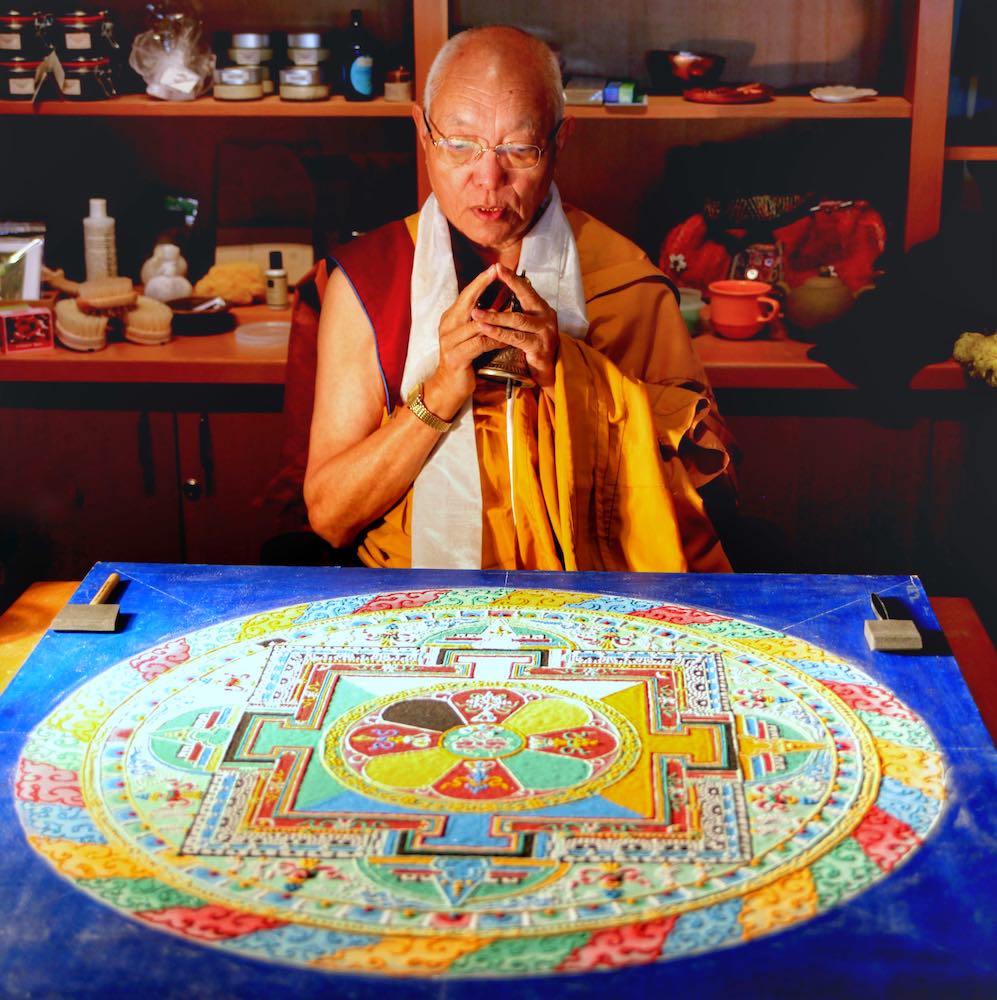

How did I manage to persevere through that difficult period, and then keep the breathing practice alive now for almost 40 years? I haven’t the slightest idea. It helped when I discovered, in the late 80s, that traditional Hatha Yoga was focused on pranayama, not on asana, as is the Iyengar way. The practice then made me feel more “authentic;” though, of course, I didn’t go “all the way” with that and do things like cut my frenulum and elongate my tongue for khechari mudra, and extract my intestines through my anus and wash them in a local river. It also helped that I became known as one of the few teachers at the time that taught pranayama, which afforded me the opportunity to teach all around the country (including in beautiful Los Gatos for the equally-beautiful Jennifer Prugh).

Along the way, around 2002, I was diagnosed with Parkinson’s, which put a serious crimp on my practice and occasioned a number of major and minor changes. I realized that all the fancy-pants manipulations of the breath were mostly unnecessary, so my practice today is pretty basic. Regardless, I’ve benefited enormously from the years of formal breathing (as I like to call pranayama today) – even the stripped down version. By far, the most important benefit has been making the acquaintance of my Witness (sakshin). Over the years, from watching my breath in my practice, I eventually expanded out into watching myself, without criticism or judgment, as I go about my daily business. The Witness encourages me to act as responsibly and “authentically” as I can, which helps me be a better human, or at least want to be, despite all my flaws.

One reply on “Why I (Still) Practice Pranayama”

I really enjoyed your article….started YTT at 63 when I retired from being an elementary teacher.

Like most if us that are teachers…we can’t get enough yoga knowledge.

Sorry about your health but glad that you continue to take care of yourself.

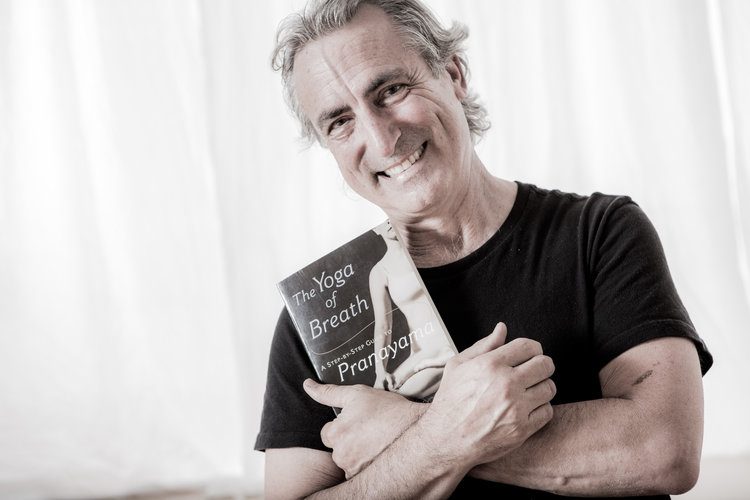

Your books look great! I will be looking into them for reading.